×

Please fill all required fields

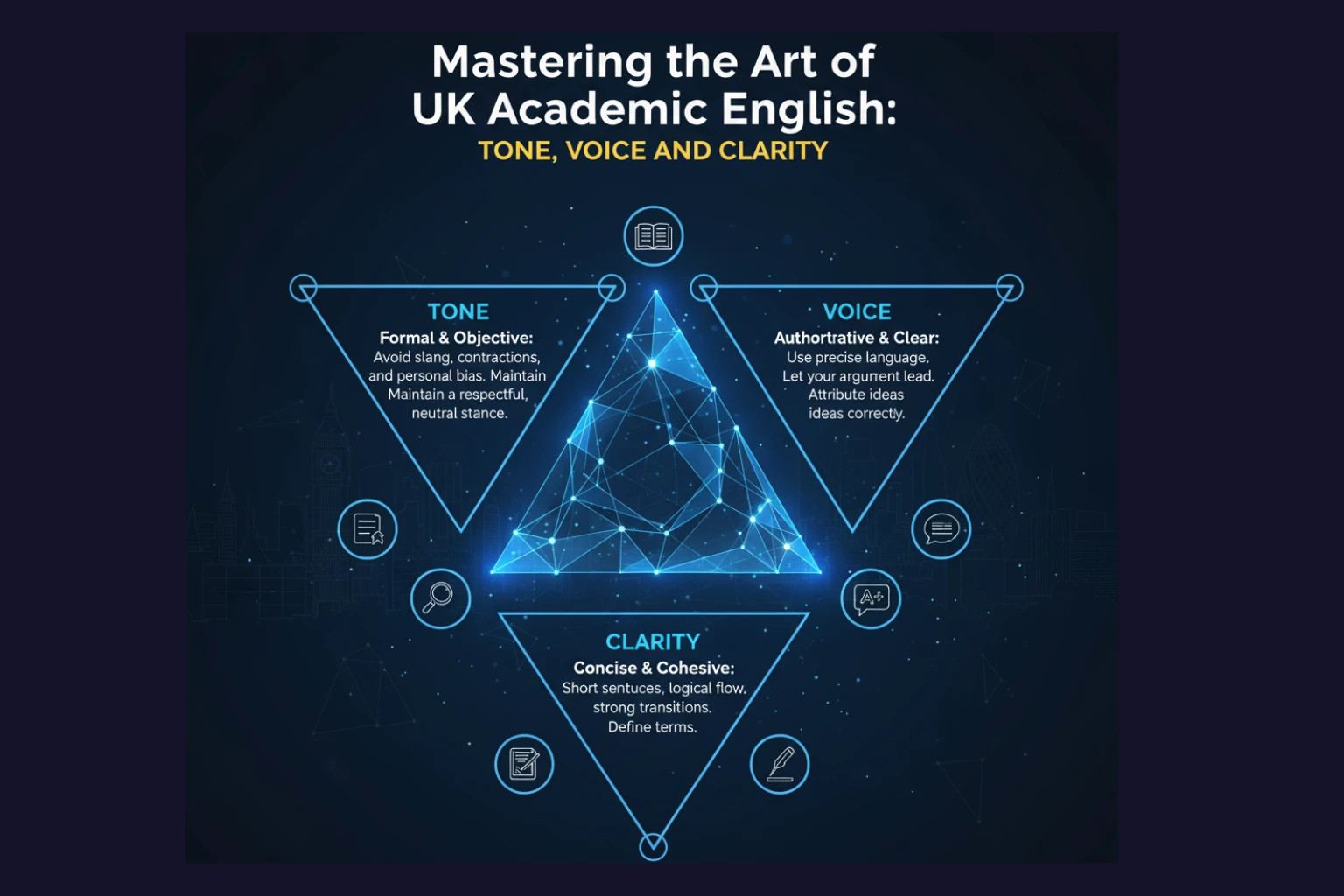

You have brilliant, original ideas. You’ve done the research and formulated your argument. But in the UK university grading system, a brilliant idea is only as good as its expression. The single greatest linguistic barrier for both native and international students isn't just grammar; it's mastering the specific academic tone, voice, and clarity that markers expect.

This style is a code. It's formal, objective, precise, and cautious. It's the difference between an argument that is perceived as insightful and one that is dismissed as simplistic.

For many students, this linguistic barrier is what separates a 2:1 from a First, or a 2:2 from a 2:1. Your ideas deserve to be communicated with the sophistication they hold. This guide will demystify the art of UK academic English, and our assignment help service will help you perfect it.

UK academic writing is not about using "fancy" words. It’s about building a formal, evidence-based argument that removes your personal bias and allows the research to speak for itself.

The first rule of academic style is to adopt an objective, impersonal tone. Your marker wants to see your analysis of the evidence, not just your personal feelings. This is achieved by removing yourself from the writing.

Before: "I think the experiment was a total failure because the results were really bad."

After: "The experiment did not yield the expected outcomes, suggesting a flaw in the methodology."

Academic markers value density. Every word must serve a purpose. Vague language and "waffle" obscure your argument and suggest a lack of clear understanding.

Before: "There are lots of different things that show this is a good idea for society."

After: "Several socio-economic factors indicate that this policy could generate positive communal outcomes."

This is one of the most vital and misunderstood skills in UK academic writing. In academia, absolute, unsupported claims are seen as naive and unscholarly. You must demonstrate intellectual caution by "hedging" your claims. This shows you understand the limitations of your research.

Use cautious language to show nuance:

Using these phrases isn't a sign of weakness; it's a mark of a mature, critical-thinking academic.

Our service goes beyond basic writing. We specialise in specific referencing styles (Harvard, APA, OSCOLA) and subject complexities, ensuring your work meets the high expectations of your module leader.

Once you have the right tone, you must connect your ideas. Sophistication lies in how you build your argument, guiding the reader logically from one point to the next.

Work that receives lower grades often relies on a monotonous series of short, simple sentences. High-level writing uses complex and compound-complex sentences to show the relationship between ideas (e.g., cause and effect, contrast, concession).

This second example doesn't just list facts; it builds an argument by linking them.

Transition words (or "signposts") are the glue that holds your essay together. They are crucial for creating a smooth, logical flow that your marker can easily follow.

Use this list to guide your reader:

| Purpose | High-Level Transition Words & Phrases |

|---|---|

| Addition | Furthermore, Moreover, In addition, Correspondingly, |

| Contrast | Conversely, in contrast, notwithstanding, however, |

| Result | Consequently, therefore, As a result, thus, |

| Concession | Although, Despite this, Nonetheless, Nevertheless, |

| Emphasis | Significantly, Notably, Crucially, Of particular note is... |

To demonstrate mastery, you must "speak the language" of your field. This means correctly using the subject-specific terminology and jargon of your discipline (e.g., "epistemology" in philosophy, "neoliberalism" in politics, "osmosis" in biology).

A crucial warning: Do not "thesaurus abuse." Using a complicated word incorrectly is far worse than using a simple word correctly. Precision and correct application are always more important than "sounding smart."

Even the most brilliant arguments can be undermined by recurring technical errors. These are the red flags that markers notice immediately and can damage your credibility.

Beyond simple typos, markers look for high-level structural errors.

This is essential for international students. Handing in a paper at a UK university with US spelling signals a lack of attention to detail.

A common point of confusion is when to use the active vs. passive voice.

Rule of Thumb:

You have read this guide because you understand that at a UK university, the quality of your writing is inseparable from the quality of your ideas.

You can have a First-Class ($70\%+$) idea, but if it is communicated with a 2:2-level ($50-59\%$) English, your marker cannot award you the top grade.

This is the "linguistic ceiling."

When a marker has to re-read your sentences to understand their meaning, your argument loses its impact. Ambiguity, poor flow, and incorrect tone create friction, preventing the marker from seeing the brilliance of your work. This is how insightful essays get stuck at $59\%$ (a 2:2) or $69\%$ (a 2:1)—they fail to meet the linguistic standards for the next classification.

This is where we come in. Our service is not a simple "grammar check." We are academic language specialists trained in the specific requirements of UK universities.

We focus on Academic English Refinement. Our assignment help, native-speaking editors will:

We ensure your complex ideas are communicated with the flawless sophistication expected for a First Class Honours.

Because academic tone signals critical thinking and professionalism. UK markers assess not just what you argue, but how precisely and objectively you communicate it. Poor tone can make even strong ideas appear underdeveloped or biased.

The UK style values linguistic caution, balanced argumentation, and subtlety. It tends to avoid absolute claims, overly confident phrasing, and overuse of first-person pronouns—features more common in US academic writing.

Formality comes from clarity, structure, and tone, not long words. Use precise vocabulary, complete sentences, and neutral phrasing. Avoid slang, contractions, or emotional expressions—but don’t overload your writing with jargon.

It means your essay might sound too descriptive, casual, or personal. Academic voice reflects confidence, objectivity, and awareness of scholarly debate. You need to sound like part of the academic conversation, not an outside observer.

After drafting, highlight any words that show personal feeling (“amazing,” “terrible,” “important to me”) or casual tone (“a lot,” “stuff,” “kind of”). Replace them with neutral, specific, evidence-based expressions.

Professional editors refine tone, clarity, flow, and argument structure. They ensure your writing meets UK academic conventions, eliminating subtle language flaws that can cap your grade even when your ideas are excellent.